This

is part 3 of a 5 part Information Guide. Introduction:

Index

BEYOND

DIAGNOSIS - THE DESERT OF DOUBT

Having assembled

all the data available about the diagnosis, the next step is to decide what treatment

to choose - if indeed treatment is required.

It

may sound like madness not to treat a disease diagnosed as cancer immediately.

But not all cancers are equal and in many cases - probably the majority, prostate

cancer is a slow growing or indolent disease which should be managed successfully

as a chronic illness. Of course no one should ever ignore a potentially dangerous

disease, but immediate action may not be essential. All treatments for prostate

cancer have a risk of side effects (termed morbidity) which can, in many cases,

significantly reduce the quality of life. It is important to ensure as far as

possible that treatment is justified and that the most appropriate treatment is

chosen.

So...

|

WHICH TREATMENT IS THE ONE FOR ME?

When faced with this question, the

traveler

through this Strange Place will discover the greatest conundrum of the disease:

THERE IS NO AGREEMENT IN THE MEDICAL

PROFESSION AS TO WHICH TREATMENT, OR COMBINATION OF TREATMENTS, IS BEST.

Relevant

scientific data from randomized studies comparing the outcomes of various treatment

options does not exist.

|

How

can this be? This excerpt from a 1997 article in The New England Journal of

Medicine, the prestigious American medical journal, sums up the position pretty

clearly:

"... we have no firm guidelines for advising our patients about which therapeutic

option is best. This means that education is more important than ever, but the

art of multidisciplinary counselling is hampered by rivalries that seem more common

among prostate cancer specialists than in other cancer specialties. This must

change…. Close collaboration between surgeons, radiotherapists, and medical oncologists

is mandatory for substantially improved control of prostate cancer."

There

is no sign of any great change since that was written more than ten years ago.

In contrast to virtually every other cancer, where oncologists are directly involved

in the choice of appropriate treatment, prostate cancer is still mainly treated

by urologists, most of whom are surgeons. They will usually recommend surgery.

If a second opinion is sought from a radiologist, radiation therapy may well be

recommended for the same diagnosis. Both can quote statistics to support their

position - how can both be right? Until this is resolved, the newcomer to this

Strange Place must make up his own mind what is best for him and choose

a course of treatment balancing risks versus reward as defined by his values -

these generally include both survival and quality of life considerations. Hopefully

what follows will help him find his way through the uncertainty of this Desert

of Doubt.

|

MORE LANGUAGE HINTS

Before

moving onto the treatment choices it is important to understand that there are

no standard definitions for words like 'cured' or 'continent' or 'impotent' -

all very important issues in the decision making process.

Much

published information avoids stating definitions and outcomes directly and as

a result, men misunderstand the odds when choosing treatment.

To

make the decision that he will not regret, a man should understand his risk of

morbidity (side effects) as well as his likelihood of a "cure" and how these terms

are defined and measured.

|

When

asked, a doctor may present percentage figures or other data regarding the likelihood

of being 'cured', 'continent', and 'potent' following the course of treatment

being recommended. It is essential to make sure that the terms used are understood.

Most men expect 'cured' to mean that the tumour has been removed and that they

will have no sign of the disease again: they do not expect to have regular PSA

checks for the rest of their lives to ensure that the treatment has not failed.

They expect 'continent' to mean that they will not leak and will be able to urinate

without problems: they do not expect to have to use pads to remain dry or a penile

clamp to stop leaking. And they expect 'potent' to mean that they will be able

to achieve erections at will, whenever required: not to have to rely on medications

such as Viagra or injections or mechanical devices. Yet studies have definitions

of 'cured', 'continent', and 'potent' that differ markedly from these expectations

and actual outcomes of treatment may be worse than they are said to be because

of this. It is also important to understand that published information will usually

show the results achieved by very skilled and experienced practitioners. Their

results will almost certainly be better than someone who does not share these

traits.

Men should be free to decide that they would rather live with the

cancer than with the side effects of being treated for it. Men choosing treatment

should not expect to be free of its side effects; men choosing Active Surveillance

should expect eventual disease progression. These factors must be weighed against

a man's expected longevity and pre-treatment situation - for example many men

develop erectile problems as they age, so loss of this function might not be a

big issue for them; a man with severe urinary problems from BPH (Benign Prostate

Hyperplasia) might welcome the relief urinating freely again after surgery, and

accept the possibility of bit of leakage. A young man diagnosed with aggressive

disease is in a much different situation from that of an older man with low to

moderate risk disease. If the probability of the tumour having spread beyond the

gland is high, the odds of a 'cure' may be so low as to be a deciding factor not

to have aggressive treatment. Family history should also be considered: sharing

genes with someone gravely affected by prostate cancer may mean a genetic increase

the risks of not being treated.

As long as the death rate from prostate

cancer stays at about one in eight for those who have been diagnosed (regardless

of stage and grade), the decision not to have immediate treatment should not be

viewed as an illogical course.

TREATMENT

OPTIONS

Treatment options vary from country to country. The greatest

variety available is in the United States of America where, it is said, there

are at least fifteen, none of which are demonstrably better than each other. The

main options and sub-sets are:

Surgery - This is the most common procedure, technically referred to as

RP (Radical Prostatectomy). The main sub-sets are "open" and "keyhole" or laparoscopic

procedures. Open surgery may be retropubic or perineal: keyhole surgery may be

manual or robotic. Men with advanced prostate cancer may have their testicles

removed surgically. This is called an Orchiectomy or an Orchidectomy, and although

a surgical procedure it is really a form of hormone treatment.

Surgery - This is the most common procedure, technically referred to as

RP (Radical Prostatectomy). The main sub-sets are "open" and "keyhole" or laparoscopic

procedures. Open surgery may be retropubic or perineal: keyhole surgery may be

manual or robotic. Men with advanced prostate cancer may have their testicles

removed surgically. This is called an Orchiectomy or an Orchidectomy, and although

a surgical procedure it is really a form of hormone treatment.

Radiation Therapy - The most common form is EBRT (External Beam

Radiation Therapy) with a number of sub-sets that refer to the method of delivering

the radiation dose. Another form of radiation therapy - Brachytherapy -

has radioactive 'seeds' introduced into the prostate gland on a permanent or temporary

basis

Radiation Therapy - The most common form is EBRT (External Beam

Radiation Therapy) with a number of sub-sets that refer to the method of delivering

the radiation dose. Another form of radiation therapy - Brachytherapy -

has radioactive 'seeds' introduced into the prostate gland on a permanent or temporary

basis

Androgen

Deprivation Therapy - This is referred to as ADT, but more commonly

known as Hormone Treatment. There are many variations on this type of treatment,

but essentially all involve using medication to suppress the hormonal mechanisms

that help tumours to grow. Orchiectomy, surgical removal of the testicles, is

an irreversible form of hormone treatment.

Androgen

Deprivation Therapy - This is referred to as ADT, but more commonly

known as Hormone Treatment. There are many variations on this type of treatment,

but essentially all involve using medication to suppress the hormonal mechanisms

that help tumours to grow. Orchiectomy, surgical removal of the testicles, is

an irreversible form of hormone treatment.

Active Surveillance - AS is often referred to as "Watchful Waiting".

No conventional treatment is undertaken unless regular monitoring indicates disease

progression. Men choosing AS often make changes to diet and lifestyle with the

intention of boosting the immune system.

Active Surveillance - AS is often referred to as "Watchful Waiting".

No conventional treatment is undertaken unless regular monitoring indicates disease

progression. Men choosing AS often make changes to diet and lifestyle with the

intention of boosting the immune system.

Cryotherapy - The prostate gland is frozen in this therapy usually referred

to as Cryo. The treatment is evolving and now includes focal cryotherapy aimed

at targeting a tumour (like a lumpectomy in breast cancer) and thus reducing the

probability of side effects. It is still regarded as somewhat experimental.

Cryotherapy - The prostate gland is frozen in this therapy usually referred

to as Cryo. The treatment is evolving and now includes focal cryotherapy aimed

at targeting a tumour (like a lumpectomy in breast cancer) and thus reducing the

probability of side effects. It is still regarded as somewhat experimental.

High Intensity Focused Ultrasound- This procedure known as HIFU uses

the heat generated by the ultrasound to focus on and destroy the tumour. Developed

in China and used for some years in some European countries, Mexico and Canada,

it is still regarded as experimental in the United States of America.

High Intensity Focused Ultrasound- This procedure known as HIFU uses

the heat generated by the ultrasound to focus on and destroy the tumour. Developed

in China and used for some years in some European countries, Mexico and Canada,

it is still regarded as experimental in the United States of America.

Chemotherapy - This treatment has not been used very much in dealing with

prostate cancer except as a last resort if all else fails. New chemicals and protocols

developed in the USA seem to be proving more effective than those in the past.

Chemotherapy - This treatment has not been used very much in dealing with

prostate cancer except as a last resort if all else fails. New chemicals and protocols

developed in the USA seem to be proving more effective than those in the past.

|

IMPORTANT INFORMATION REGARDING TREATMENT CHOICE

1.

Be certain that immediate treatment is required. Some leading experts in the

US say that the substantial majority of treatment procedures carried out for prostate

cancer in the US are unnecessary - estimates vary between 25% and 80%.

2.

The choice of treatment may be less important than the choice of who does the

procedure. The non-medical people in the prostate cancer community generally

agree the experience of the person or team carrying out the chosen procedure is

of utmost importance. The more experience, the less severe the side effects. This

may seem obvious, but many men only find out the hard way. It may be embarrassing

to ask a surgeon or radiologist to provide evidence of their skill, but bearing

in mind the consequences, this question should never be avoided.

3.

It is important to be as certain as possible that the disease is contained within

the prostate capsule before making any final treatment decision. This is where

the Partin Tables and other similar nomograms are very useful. The information

obtained by using the Partin Tables is no guarantee of the actual situation for

any individual. It does however provide some indication of what treatment options

might achieve the best result, and which might be ruled out because of the possible

extent of disease.

|

There

is need at this point for a short diversion to consider the tables before getting

back to the discussion of treatment choices.

Diversion

to consider the Partin Tables:

Allan W. Partin, M.D., Ph.D., and

Patrick C. Walsh, M.D. at the James Brady Urological Institute in Boston, USA

developed these tables which are based on the analysis of many biopsies. Their

aim was to try to establish if there was any relationship between the various

aspects of diagnosis and the likelihood of the disease having moved beyond the

capsule. The tables are too complex to reproduce in this document, but essentially

they look at the three main aspects of diagnosis - PSA (Prostate Specific Antigen),

Gleason Score and Clinical Staging - and show, as a percentage, the statistical

likelihood of the disease having escaped the capsule or being contained.

To

take the example referred to above, where the man was diagnosed as PSA 7.2: GS

3+2=5: Stage T2bNXM0, and referring to the relevant section of the Partin

Tables we would find the chances of:

o Organ-Confined Disease are Between

55% and 68% (median 62%)

o Established Capsular Penetration are Between 26%

and 38% (median 32%)

o Seminal Vesicle Involvement are Between 3% and 8% (median

5%)

o Lymph Node Involvement are Between 0% and 2%(median 1%)

To give

some idea of how one item might change these percentages, and how important the

Gleason Score is, if the diagnosis was PSA 7.2: GS 4+4=8: Stage T2bNXM0,

then the chances above would change to these:

o Organ-Confined Disease

Between 17% and 33% (median 24%)

o Established Capsular Penetration Between

29% and 48% (median 38%)

o Seminal Vesicle Involvement Between 16% and 39%

(median 27%)

o Lymph Node Involvement Between 3% and 20%(median 10%)

There

is a lower probability of benefit from surgery or other local treatments, if there

is a high probability of the disease having escaped from the organ.

Now,

back to treatment choices:

SURGERY: This

treatment is technically called RP (Radical Prostatectomy), and is often referred

to as the "gold standard" treatment, implying it is the very best. It is the treatment

most commonly prescribed for younger men or early stage prostate cancer. The traditional

surgery was an "open" procedure but there is enormous and rapid growth in laparoscopic-

'keyhole' - surgery, especially the Da Vinci robotic procedure.

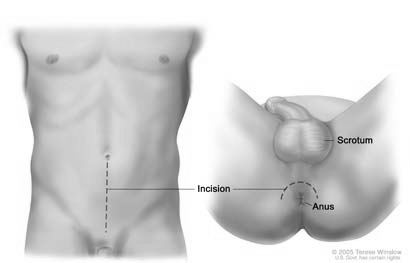

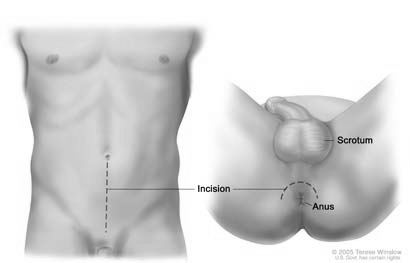

In open

surgery, the prostate gland is reached either from the lower part of the front

of the body - this is a retropubic procedure - or through the area between the anus and the

scrotum - this is a perineal procedure. There are no studies that show either

of these procedures to be superior to the other. In the past the operation involved

a substantial loss of blood. There have been significant improvements in surgical

techniques and it is now unusual for a transfusion to be required. Some surgeons

recommend the drawing and storing of the patient's own blood ahead of the operation

as a precautionary measure.

|

Retropubic Surgery

|

Perineal Surgery

|

Laparoscopic portholes

Laparoscopic

surgery on the other hand requires five small ( five to 10 millimeters) incisions

(or portholes), one just above or below the belly button and two each on both

sides of the lower abdomen. Four arms are inserted into the portholes, three hold

instruments, the fourth holds the camera - this is the laparoscope which enables

the surgeon to get pictures of the prostate on a video monitor. Carbon dioxide

is passed into the abdominal cavity through a small tube placed into the incision

below the belly button. This gas lifts the abdominal wall to give the surgeon

a better view of the abdominal cavity once the laparoscope is in place. The arms

are used by the surgeon to remove the gland, through one of the portholes and

are manipulated manually, except where the procedure is robotic assisted - a procedure

usually referred to as the Da Vinci procedure. The surgeon sits at the console

and looks through two eye holes at a 3-D image of the procedure, meanwhile maneuvering

the arms with two foot pedals and two hand controllers. The Da Vinci System translates

the surgeon's hand movements into more precise micro-movements of the instrument.

Laparoscopic

surgery on the other hand requires five small ( five to 10 millimeters) incisions

(or portholes), one just above or below the belly button and two each on both

sides of the lower abdomen. Four arms are inserted into the portholes, three hold

instruments, the fourth holds the camera - this is the laparoscope which enables

the surgeon to get pictures of the prostate on a video monitor. Carbon dioxide

is passed into the abdominal cavity through a small tube placed into the incision

below the belly button. This gas lifts the abdominal wall to give the surgeon

a better view of the abdominal cavity once the laparoscope is in place. The arms

are used by the surgeon to remove the gland, through one of the portholes and

are manipulated manually, except where the procedure is robotic assisted - a procedure

usually referred to as the Da Vinci procedure. The surgeon sits at the console

and looks through two eye holes at a 3-D image of the procedure, meanwhile maneuvering

the arms with two foot pedals and two hand controllers. The Da Vinci System translates

the surgeon's hand movements into more precise micro-movements of the instrument.

RP,

whether open or laparoscopic is a major surgical procedure and will usually take

3 to 4 hours. Discharge from hospital was normally within 3 to 5 days for the 'open'

procedures but is now likely to be 3 or less. Laparoscopic surgery, on the other

hand, is far less traumatic and men are usually discharged from hospital in 24

hours. There is still a good deal of disagreement about the merits of the two

procedures. Surgeons favouring open surgery say that they can feel the prostate

and get a better idea of where the tumour might be and thus have more assurance

of negative margins: doctors favouring laparoscopic surgery say that the better

view obtained through the magnifying lens enables them to cut and stitch more

accurately. As yet there are no long term studies to support either view. The

incidence of initial morbidity are similar as are early failure rates. One thing

has become clear - the learning curve for the laparoscopic procedure is a long

one. One published study implies that it takes at least 250 procedures before

the surgeon can be regarded as proficient.

In

either case, a catheter will be in place, usually for some weeks. It normally

takes about three months to regain control of the bladder function, although some

men achieve this sooner. Recovery of erectile function will almost certainly take

a good deal longer, many months and sometimes a year or more. Recovery of erectile

function is dependent to a large extent on the ability of the surgeon to spare

the erectile nerves, although this is not the only factor.

The main benefit

of surgery is that it introduces an element of certainty. The prostate gland can

be examined closely to establish the extent of the tumour, to verify the Gleason

Score and to clarify the likelihood of the tumour being contained within the gland.

If there has been no spread beyond the gland, then the removal of the prostate

should, by definition, remove the tumour. For many men that is of utmost importance.

However,

surgery may not be a good choice if the disease has metastasised - that is if

the disease has spread to distant sites beyond the prostate. There is a view that,

in such cases, the removal of the gland and the main tumour may accelerate the

growth of the secondary, metastasised, tumours and make control of the disease

much more difficult. Like many other aspects of prostate cancer, there is no consensus

on this issue, which is the subject of some debate among physicians and researchers.

Because it is so difficult to establish beyond doubt whether the disease has spread

beyond the gland, there may be an element of risk in opting for surgery.

Success

or "cure" is measured by taking PSA tests at intervals after the surgery. Ideally

there should be no PSA measurement detectable with the normal PSA test. Ultra-sensitive

PSA tests may show very low levels - well below 0.10 ng/ml. No formal studies

have demonstrated the superiority of surgery over other forms of therapy, including

Active Surveillance, in early stage cancer. There is a failure rate of about 30%

- 35% over a period of 10 - 15 years for men undergoing surgery. Some failures

have been reported at 20 years. In the event of recurrence or failure of the treatment,

it is possible to use EBRT (External Beam Radiation Therapy) to treat recurrence

thought to be confined to the prostate bed, or to use ADT (Androgen Deprivation

Therapy) as a secondary treatment for recurrence where the disease has spread

into other areas of the body.

The main side effects of surgery are erectile

dysfunction (the difficulty or inability to have an erection) and bladder incontinence

(the inability to control the bladder). The man also becomes infertile, since

there is no ejaculate following the removal of the gland. Men intending to father

children should bank sperm before surgery.

The first of these problems

- erectile dysfunction (ED) - comes about because the nerves controlling erections

are embedded near the surface of the prostate gland; one on each side of it. There

has been a reduction in the reported rates of erectile dysfunction following the

development of what is referred to as the "nerve-sparing" technique and the use

of pharmaceutical drugs such as Cialis, Levitra or Viagra or one of the injectable

materials - MUSE, Tri-Mix and the like. However, the position of the tumour may

affect the ability of even the best surgeon to spare one or both of the nerves

while removing all the cancer. The ED rate is still high - probably over 50%,

especially for men over the age of 50. Studies quoted with better rates should

be examined very carefully, especially for definitions of potency or erectile

function. These studies usually involve excellent surgeons and may not reflect

the general outcome of surgeries carried out by surgeons with less experience.

Total

bladder incontinence is reported in a small number of men - about 5% - but many

men experience some leakage, particularly during sexual arousal or when lifting,

coughing, sneezing or laughing. Again it is important to look at definitions when

considering studies showing levels of continence after treatment. It is not uncommon

for the use of 'only' one or two pads a day to be regarded as fully continent

in such studies. The outcomes of surgery carried out by urologists who do not

have the experience of surgeons in a centre of excellence are usually worse.

Another

issue to be aware of is stricture from scar tissue, which can also cause urinary

problems. If the man has a history of poor scarring (some reports suggest that

if any scar on his body is more than 10 mm (about 3/8") wide) then there is about

an eightfold increase in urinary problems following RP (Radical Prostatectomy).

Penile shrinkage is also reported in a significant number of men, thought

to be the result of maintaining the penis in the flaccid state during what can

be many months of recovery of erectile function. It is thought this can be counteracted

by stimulating erections with drugs or manual devices as soon as post-surgical

healing has taken place.

A final issue, rarely discussed, is that of Peyronie's

Disease or Peyronie's Syndrome. This condition is one where the erect penis acquires

a 'bend' or deflection. The vast majority of Peyronie cases are very mild but

others can cause severe problems. It seems unlikely that the condition is directly

caused by a disease, or that it has any direct link with prostate cancer. A common

cause is thought to arise from accidents during sexual activities, especially

if the penis is not fully erect.

RADIATION

THERAPY - most common form of Radiation Therapy is known as EBRT (External

Beam Radiation Therapy). There are many other acronyms, such as RT (Radiation

Therapy), IMRT (Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy) and 3DRT. All refer to

the procedure where photon radiation is directed at the site of the prostate gland

from an external source. The variations usually refer to the different aiming

techniques. A form of EBRT known as CyberKnife® delivers what are termed hypofractionated

doses - fewer doses, very much larger than normal EBRT but, it is claimed, delivered

more accurately and thus reducing the potential for collateral damage. A significantly

different form of EBRT is PBT (Proton Beam Therapy). It is claimed that the proton

beams can be directed more accurately than photon beams, again with less likelihood

of collateral damage. PBT for prostate cancer is only done at a few sites, mostly

in the US.

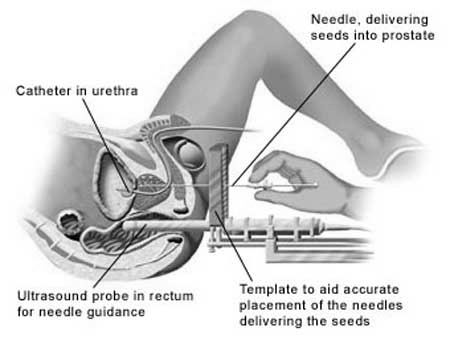

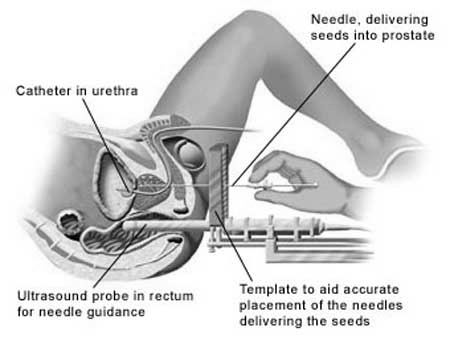

Another

form of radiotherapy, is Brachytherapy or SI (Seed Implants). Radioactive "seeds"

are implanted directly into the prostate gland, where they remain. There is a

variation of this treatment known as HDR (High Dose Rate Brachytherapy) where

seeds are inserted and then removed.

All

radiation therapy is intended to destroy the cancer cells while leaving healthy

tissue intact and is often the recommendation for older men for whom surgery presents

a health risk. EBRT is also used where it is felt that the tumour has spread beyond

the prostate gland and as a "salvage" treatment for failed surgery. EBRT used

in conjunction with other treatments such as surgery or brachytherapy is known

as adjuvant treatment. Radiation treatment is not recommended for men who have

a high International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) prior to treatment. This signals

severe urinary problems. Radiation therapies will often exacerbate these problems.

The International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) is generated from what is termed

a LUTS test (lower urinary tract symptoms).

EBRT takes place over a number

of weeks - usually six or seven - with daily sessions of therapy, the exception

being CyberKnife® which takes about five days. The effect of radiation is cumulative,

so low doses given on a regular basis build up into high doses, lethal to the

tumour cells. Most men tolerate the procedure very well, although as time goes

by, they may feel fatigued and it may be desirable to rest in the afternoon. The

feeling of fatigue will usually disappear after completion of the treatment.

Illustration of placement of seeds into prostate in brachytherapy procedure

Illustration of placement of seeds into prostate in brachytherapy procedure

Brachytherapy

is usually considered as an alternative to surgery for men with a suitable diagnosis.

SI is a relatively short procedure, taking two or three hours, after which the

man can go home and carry on with his normal activities: HDR might need an overnight

stay in hospital. There is sometimes a feeling of fatigue, as is the case with

EBRT, but this usually recedes with time, as the dosage from the seeds reduces

(they are only fully active for about six months). Brachytherapy is not a good

option for a man who has previously had a TURP (Transurethral Resection of the

Prostate).

Two

aspects of SI could cause some concern. Firstly, the man is carrying radioactive

seeds in his prostate and the question asked is whether those seeds can injure

anyone close to the man - for example, grandchildren sitting on his lap. Studies

have demonstrated this is not a risk. The second point concerns seeds migrating

from the prostate to other parts of the body, notably the lungs. This happens

when seeds work their way out of the prostate before the glandular tissue heals

and locks them in place, or where they have not been securely placed. It is said

this does not present any significant problem for the patient.

Success

or "cure" for radiation treatments is measured by a gradual reduction in PSA level

in the months after treatment is completed. The aim is to achieve a nadir, or

low point, of 0.200 ng/ml and to maintain that level. Some authorities feel a

nadir of under 1.00 ng/ml is an acceptable level. Some men experience what is

referred to as a "bump" about 18 months after radiation when the PSA rises and

then falls again. No formal studies have demonstrated the superiority of radiation

therapy over other forms of therapy, including Active Surveillance. There is a

failure rate of about 30% - 35% over a period of 10 - 15 years for men undergoing

radiation therapy. A leading US institution claims better long-term freedom from

disease using combined SI/EBRT therapy rather than EBRT alone. They term this

treatment procedure as ProstRcision®.

In the event of recurrence or failure

of radiation treatment, surgery is not a good option and is rarely successful

because of the damage done to the tissue by the procedure. The usual option for

further management is ADT (Androgen Deprivation Therapy) although Cryotherapy

can also be used as a salvage treatment.

The side effects of radiation

therapy are similar to surgery with the added complication of urinary urgency/frequency,

difficulty in starting a urine stream and incontinence. Radiation can sometimes

result in bowel incontinence as well as rectal bleeding. ("Incontinence" is the

inability to control bladder or bowel). The reported incidence of bowel incontinence

is fairly low for EBRT and even lower for SI and PBT. There is a reported improvement

in radiation treatment side effects with modern techniques. Erectile dysfunction

is reported to occur in a substantial number of cases, more so for EBRT than SI,

but at about the same level as surgery. In contrast to surgery, where an immediate

loss of function can be followed by a gradual recovery, erectile dysfunction associated

with radiation therapy of any kind tends to occur well after treatment and to

gradually grow worse over time.

ADT (ANDROGEN

DEPRIVATION THERAPY) generally known as Hormone Treatment. There are

many variations of this treatment, all with different acronyms. The theory behind

this treatment is that growth of prostate cancer cells is fuelled by dihydrotesterone

(DHT) a derivative of testosterone, the male hormone steroid, which is an androgen.

A reduction in the production of androgen will therefore theoretically deprive

these cells of nutrition and they will die. There are four methods by which the

cells are deprived of androgen.

Ablation. The testes produce approximately 90% of the male body's testosterone

with the balance being produced by the adrenal glands. Thus a simple way to reduce

testosterone production is the surgical removal of the testes by way of an orchiectomy

or orchidectomy (castration).

Ablation. The testes produce approximately 90% of the male body's testosterone

with the balance being produced by the adrenal glands. Thus a simple way to reduce

testosterone production is the surgical removal of the testes by way of an orchiectomy

or orchidectomy (castration).

Additive. Testosterone production is attacked by dosing the man with oestrogen.

Additive. Testosterone production is attacked by dosing the man with oestrogen.

Inhibitive.

This involves the use of chemicals to block signals from the brain to the production

centres so that no testosterone is produced.

Inhibitive.

This involves the use of chemicals to block signals from the brain to the production

centres so that no testosterone is produced.

Competitive. The final method of treatment involves what are known as antiandrogens.

These do not prevent the production of testosterone, but block the receptors on

the prostate gland, preventing the androgen from being absorbed.

Competitive. The final method of treatment involves what are known as antiandrogens.

These do not prevent the production of testosterone, but block the receptors on

the prostate gland, preventing the androgen from being absorbed.

The last

three treatments are sometimes used in unison, in which case the treatment is

referred to as CHT (Combined Hormone Therapy) or ADT3. Treatment is administered

in a variety of forms, from pills to monthly or quarterly injections.

ADT

was at one time only used to manage late stage prostate cancer, where the tumour

had spread beyond the capsule and therefore could not be treated by surgery or

radiation and/or as a "salvage" therapy for failed surgery or radiation treatment.

There is however a growing use of this therapy as a precursor to other treatments.

This is known as neo-adjuvant therapy. Many practitioners are opposed to this

practice because studies do not show any significant advantage for the inevitable

side effects and there are several disadvantages. Some leading practitioners of

both surgery and brachytherapy in the US will not treat men who have had this

neo-adjuvant therapy.

The aim of ADT is to manage and control the disease,

since it is extremely unlikely that this therapy will result in a permanent "cure".

The degree of success achieved is measured by the reduction of the PSA to as low

a level as possible and keeping it there. In many cases the PSA level can be undetectable

and there are reports of men treated with this therapy achieving mortality rates

very similar to those of men without the disease. Failure of this treatment occurs

when the tumour becomes androgen independent (AI). This condition is often referred

to as AIPC - Androgen-Independent Prostate Cancer, or Hormone Refractory Prostate

Cancer (HRPC). This means the tumour has found a way of growing without the androgen

associated with testosterone. Management of the disease at such a stage is very

difficult although some success has been reported with new chemotherapy drugs.

There

are numerous side effects associated with this form of treatment whether the treatment

is being used as an adjuvant treatment for early stage tumours or as a palliative

measure for advanced cancers. Some men have severe side effects, others have

none: some appear early, some only after a long period of treatment. The ones

reported most frequently by men undergoing any of the ADT methods are erectile

dysfunction, loss of libido (no interest in sexual activity), hot flushes, osteoporosis

(loss of bone), loss of muscle tone, weight gain and mood swings, with depression

being widely reported.

Individual methods have other side effects such

as the development of breasts, increased risk of thrombosis, and an initial rise

in tumour activity, known as a "flare". This is usually of a temporary nature.

Flare can be prevented by administering an anti-androgen one week prior to the

first injection of the drug being used to inhibit testosterone production.

A

list of potential side effects associated with ADT include:

Alcohol intolerance

(with Casodex and Eulexin); Anaemia; Anxiety or depression; Arthritic symptoms;

Appetite loss; Blood in urine; Breast swelling and tenderness (gynecomastia);

Cholesterol and triglyceride increase; Constipation; Diarrhoea (eulexin); Disturbed

sleep; Drowsiness; Dry mouth; Emotional instability (esp. Crying); Feet or lower

legs, swelling of (peripheral oedema); Flatulence; Flu syndrome; Hair: decrease

in pubic and axillary hair; facial hair grows more slowly; Headache; High blood

pressure (hypertension); Hot flushes; Hyperglycaemia (high blood sugar ); Impotence

(during the period of treatment and some months after); Indigestion; Itching;

Insomnia; Liver problems; Memory loss; Methemoglobinemia (a crystallization in

the blood); Nausea; Nocturia (need to urinate frequently at night); Nervous and

twitchy legs; Osteoporosis; Pain: abdominal, back, chest, in right side; Pressure:

feeling of extreme pressure in head; Prickling sensation on the skin; Shortness

of breath; Testicular atrophy (shrinking) & soreness; Sweating; Weight gain (weight

gain may continue for a while after treatment); Weight loss.

|

SERIOUS

ADT SIDE EFFECTS

The

following symptoms may reflect serious problems and if they occur, medical attention

should be sought immediately:

Bluish lips, fingernails, or palms of hands;

Dizziness (extreme) or fainting; Fatigue, weakness; Pain: bone, joints, pelvic;

Numbness, coldness, or tingling of hands or feet; Infections; Rash; Urinary incontinence;

Urinary tract infection; Vomiting; Weak and fast heartbeat; Yellow eyes or skin.

|

A

recent development has been towards "pulse" therapy known as IHT (Intermittent

Hormone Treatment) or IHB (Intermittent Hormone Blockade). Some studies indicate

that stopping the ADT once the PSA count has been reduced and reintroducing the

therapy if the PSA count rises again might produce some benefit. The duration

of the side effects of ADT are reduced and it appears the possibility of the disease

becoming androgen-independent may also be lessened. In some very rare cases, the

PSA does not rise again after the ADT is stopped and the man can be considered

to be in remission. Men on ADT welcome the treatment "holidays" as many of the

side effects disappear or diminish as the effect of the drugs wears off. In some

cases some of the side effects are permanent.

CRYOTHERAPY:

This procedure uses probes to freeze the gland. The prostate tissue is destroyed

by the very rapid thawing process which ruptures the cell membranes. The probes

are placed through the perineal skin - between the scrotum and anus, like the

tubes for brachytherapy. They are guided using transrectal ultrasound which is

also used to monitor the freezing process in real time. It is unusual for fewer

than three probes to be placed; additional probes may be placed to allow for adequate

freezing of more extensive disease. Incontinence levels are kept low by warm liquid

being circulated in the urethra during the procedure.

When this procedure

was first used, the entire gland was destroyed, which led to a very high incidence

of erectile dysfunction - almost 100% of men were impotent according to some studies.

Later developments have seen the development of focused cryotherapy, which destroys

only identified tumours and the healthy cells in the immediate vicinity of the

tumour, leaving some or all of the erectile nerves untouched and resulting in

levels of ED that are comparable with those resulting from other treatments. It

can be difficult to pinpoint the position of small tumours. This usually involved

a mapping biopsy using a large number of needles - as a rule of thumb the volume

of the gland + 20 up to a potential maximum of 100 needles. This type of biopsy

is usually undertaken under a general anaesthetic. .

One advantage this

form of treatment has is that it can be repeated and it can be used in suitable

cases as a salvage procedure for other failed treatments, notably radiation.

HIGH

INTENSITY FOCUSED ULTRASOUND (HIFU): This procedure was developed in China

and used for liver and pancreatic cancers, but was not used initially for prostate

cancer. Subsequently several European countries, notable, France, Germany and

Belgium started to treat men with prostate cancer. Basically the tumors are cooked

to death quickly. The focused sound energy raises the temperature to around 140

degrees Fahrenheit (60 degrees Celsius), killing the cells in about one second.

The ultrasound beam must travel through continuous tissue or fluid to the tumor

site because the energy cannot be focused through gas or bone. By targeting tumour

cells precisely, theoretically the tumor can be destroyed with minimum collateral

damage. Like cryotherapy one of the immediate pre-treatment issues is how to identify

the precise location of the cancerous cells.

HIFU is still regarded as

experimental in a number of countries and has not been approved for prostate cancer

by the FDA in the USA. Trials are being carried out there.

There

have been alarming reports of bladder damage creating severe urinary problems.

It is clear that experience with the equipment used for this therapy is even more

important than in other therapies. An unskilled practitioner can do a deal of

damage very quickly.

ACTIVE SURVEILLANCE:

This option is still often referred to as WW (Watchful Waiting) although the terms

have different meanings. In the past Watchful Waiting meant no action was undertaken

unless the disease is seen to progress. Men choosing the Active Surveillance are

monitored closely and will often use a variety of non-conventional or alternative

treatments to manage the progression of the disease.

Dr.

Jon Oppenheimer, a leading pathologist in the USA is on record as saying:

"For

the vast majority of men with a recent diagnosis of prostate cancer the most important

question is not what treatment is needed, but whether any treatment at all is

required. Active surveillance is the logical choice for most men (and the families

that love them) to make."

|

The

rationale for this statement is that prostate cancer is what is termed an "indolent"

disease in most cases, because it progresses so slowly it may never be a threat

to life. The man choosing Active Surveillance over Watchful Waiting believes by

taking a proactive stance he can harness his immune system to either halt the

progress of the disease or possibly even cause it to regress.

Prime

candidates for this option are those who have been diagnosed with an insignificant

tumour or very low risk disease. There are various definitions of these terms,

but broadly speaking they are similar to the one established by Johns Hopkins

University School of Medicine in the US, where the definition of an insignificant

tumour was established some years as one with the following characteristics:

Nonpalpable - the examining doctor would not feel anything when carrying

out the DRE (Digital Rectal Examination)

Nonpalpable - the examining doctor would not feel anything when carrying

out the DRE (Digital Rectal Examination)

Stage T1c - the tumour is discovered in the course of a biopsy following

an elevated PSA test where there are no other symptoms

Stage T1c - the tumour is discovered in the course of a biopsy following

an elevated PSA test where there are no other symptoms

Free PSA - the percentage of free PSA should be 15% or greater

Free PSA - the percentage of free PSA should be 15% or greater

Gleason Score - less than 3+4=7 - or, as some practitioners have it, 7 or

less

Gleason Score - less than 3+4=7 - or, as some practitioners have it, 7 or

less

Size - less than three needle cores positive with none greater than 50%

tumour. (In this definition it is assumed that a 12 needle biopsy is used)

Size - less than three needle cores positive with none greater than 50%

tumour. (In this definition it is assumed that a 12 needle biopsy is used)

The

latest guidelines issued by National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN®) following

the codified changes to the Gleason grading system in January 2009 has this definition

of very low risk disease:

Clinical Stage T1-T2a - the examining doctor felt nothing on DRE or felt

something on one side of the gland only

Clinical Stage T1-T2a - the examining doctor felt nothing on DRE or felt

something on one side of the gland only

Gleason Score 6 - the lowest score on the current range

Gleason Score 6 - the lowest score on the current range

PSA less than 10 ng/ml

PSA less than 10 ng/ml

Size - 3 positive needles or less with 50% or less positive material in each

core

Size - 3 positive needles or less with 50% or less positive material in each

core

PSA density - less than 0.15 ng/ml/gm

PSA density - less than 0.15 ng/ml/gm

Old

studies have shown the majority of men with such a diagnosis will not have a life-threatening

progression of the disease for many years. Current studies demonstrate that there

is a negligible risk for suitable men in undertaking Active Surveillance.

The

precise protocols for men choosing Active Surveillance vary, but broadly speaking

they involve regular PSA tests (every man diagnosed with prostate cancer will

continue to have these tests for the rest of his life to monitor him for any progression

or return of the cancer) and other tests, notably biopsy procedures and DRE (Digital

Rectal Examinations). Initially these may be done annually, but there is a view

that once it has been established that the disease shows no sign of progression,

the period between procedures may be extended. Other tests and scans, such as

Color Doppler scans may be used to monitor significant changes in the tumour.

Because

men choosing Active Surveillance have still have an untreated, entire gland they

may therefore have to deal with issues such as BPH (Benign Prostate Hyperplasia)

- the enlargement of the gland which causes urinary problems. BPH can be successfully

managed with a variety of drugs or procedures such as a TURP (Trans Urethral Resection

of the Prostate) - often referred to as a 'rotor rooter' operation .

The

problem for any man considering Active Surveillance is the uncertainty of the

diagnostic process, which is more art than science. It is not possible to identify,

with absolute certainty, which tumours are indolent (the kitty cats) and which

are aggressive (the tigers) or just where they fit in the range of diseases. There

are good indicators: The ones listed above indicate disease that is most likely

indolent; on the other hand PSA doubling times measure in months or weeks, high

Gleason Scores - over 20 ng/ml, late stage disease - stages T3 and T4 all indicate

a disease that requires early attention. Indolent disease can often be treated

like a chronic illness.

For

many men choosing this course, the essence of Active Surveillance is a belief

in the mind/body continuum. The aim is to maintain the immune system in good condition

to deal with the tumour. Since there are very few studies to guide men in this

endeavour, and the medical professionals are often ill-informed on nutritional

matters and similar issues, there is a tendency for each man to develop his own

unique program. Most of the programs for which there is anecdotal support include

the following elements:

Stress reduction: Stress is commonly regarded as one of the most

universal causes of damage to the immune system. Stress reduction can be accomplished

using activities such as meditation, visualisation or yoga.

Stress reduction: Stress is commonly regarded as one of the most

universal causes of damage to the immune system. Stress reduction can be accomplished

using activities such as meditation, visualisation or yoga.

Exercise: Moderate amounts of exercise are essential. Usually, subject

to the fitness of the man, he is recommended to exercise at least three days a

week at a level where the pulse rate is raised and sweat is formed.

Exercise: Moderate amounts of exercise are essential. Usually, subject

to the fitness of the man, he is recommended to exercise at least three days a

week at a level where the pulse rate is raised and sweat is formed.

Changes in diet: This subject is covered in a little more depth

in the section titled Plains of Recovery, but essentially, the aim is to

attain a vegetarian diet or better still a vegan diet. Red meat and dairy products

are regarded as bad: fresh vegetables and fruit are regarded as good. Smoking

should, of course, be stopped, as should consumption of alcohol, although small

quantities of wine, especially red wine, are thought to be beneficial. Consumption

of coffee, animal fats, fried foods and sugar should be kept to a minimum.

Changes in diet: This subject is covered in a little more depth

in the section titled Plains of Recovery, but essentially, the aim is to

attain a vegetarian diet or better still a vegan diet. Red meat and dairy products

are regarded as bad: fresh vegetables and fruit are regarded as good. Smoking

should, of course, be stopped, as should consumption of alcohol, although small

quantities of wine, especially red wine, are thought to be beneficial. Consumption

of coffee, animal fats, fried foods and sugar should be kept to a minimum.

Weight loss: There is a clear connection between illness and obesity.

Although following the steps above should lead to weight loss, this should also

be incorporated as one of the aims of any successful program.

Weight loss: There is a clear connection between illness and obesity.

Although following the steps above should lead to weight loss, this should also

be incorporated as one of the aims of any successful program.

Successful

Active Surveillance management should see a stabilising or even a reduction in

PSA levels, and this is the primary measure of success. Because of the vagaries

of PSA counts, this should not however be the only measure. There should also

be an annual DRE (Digital Rectal Examination) and, some recommend, an annual or

biennial biopsy. In considering this latter test, some thought should always be

given to the potential for side effects from biopsy. A continuous rise in PSA

or a positive DRE would be the trigger to contemplate further, conventional treatment.

Many men - more than 20% in one study - who have chosen Active Surveillance have

negative biopsy results on repeat biopsy. This does not necessarily mean that

there are no longer cancer cells in the gland, because the biopsy process is literally

'hit and miss' but it does imply that there has been little or no significant

growth in the tumour.

The side effects of a successful Active Surveillance

program are all positive since the enhanced immune system will generally result

in better health all round.

It is often difficult to deal with the uncertainty

associated with Active Surveillance. This is often seen to be greater than the

uncertainty of those who have had conventional treatment. However in three studies

it has been found that essentially, if men are 'worriers' they have similar levels

of concern whatever the path they choose. Those who are more phlegmatic accept

the uncertainty more easily.

Anyone

embarking on Active Surveillance will need determination to continue. The medical

profession along with well-meaning friends and relatives, often create a good

deal of pressure to 'do something'. This leads many men to abandon Active Surveillance

and opt for conventional treatment even if there is no significant change in the

diagnostic pointers.

|

Back to top

GO

NOW to Part 4 - Beyond Treatment - The Plains of Recovery

Laparoscopic

surgery on the other hand requires five small ( five to 10 millimeters) incisions

(or portholes), one just above or below the belly button and two each on both

sides of the lower abdomen. Four arms are inserted into the portholes, three hold

instruments, the fourth holds the camera - this is the laparoscope which enables

the surgeon to get pictures of the prostate on a video monitor. Carbon dioxide

is passed into the abdominal cavity through a small tube placed into the incision

below the belly button. This gas lifts the abdominal wall to give the surgeon

a better view of the abdominal cavity once the laparoscope is in place. The arms

are used by the surgeon to remove the gland, through one of the portholes and

are manipulated manually, except where the procedure is robotic assisted - a procedure

usually referred to as the Da Vinci procedure. The surgeon sits at the console

and looks through two eye holes at a 3-D image of the procedure, meanwhile maneuvering

the arms with two foot pedals and two hand controllers. The Da Vinci System translates

the surgeon's hand movements into more precise micro-movements of the instrument.

Laparoscopic

surgery on the other hand requires five small ( five to 10 millimeters) incisions

(or portholes), one just above or below the belly button and two each on both

sides of the lower abdomen. Four arms are inserted into the portholes, three hold

instruments, the fourth holds the camera - this is the laparoscope which enables

the surgeon to get pictures of the prostate on a video monitor. Carbon dioxide

is passed into the abdominal cavity through a small tube placed into the incision

below the belly button. This gas lifts the abdominal wall to give the surgeon

a better view of the abdominal cavity once the laparoscope is in place. The arms

are used by the surgeon to remove the gland, through one of the portholes and

are manipulated manually, except where the procedure is robotic assisted - a procedure

usually referred to as the Da Vinci procedure. The surgeon sits at the console

and looks through two eye holes at a 3-D image of the procedure, meanwhile maneuvering

the arms with two foot pedals and two hand controllers. The Da Vinci System translates

the surgeon's hand movements into more precise micro-movements of the instrument. Illustration of placement of seeds into prostate in brachytherapy procedure

Illustration of placement of seeds into prostate in brachytherapy procedure