This

is part 2 of a 5 part Information Guide.Introduction:

Index

GETTING

STARTED - THE FOREST OF FEAR

Going through the process of diagnosis

is a frightening experience for most. Tests are ordered, often without any apparent

reason or explanation; results are given in language that is difficult to interpret

or understand; and all the time the fear grows. Hopefully, this section will take

some of that fear away from the process. There is also often a feeling that time

is limited, that a decision regarding treatment must be made very soon after diagnosis.

For the vast majority of men the window of opportunity for successful treatment

is a wide one and decision-making may safely take some months.

|

The

first important fact about all medical tests:

No test is 100%

accurate. Diagnosis is not an exact science.

|

The

degree of error can vary considerably, depending on the complexity of the test

- and some tests are very complex indeed. Sophisticated machinery is used for

some - the maintenance of the machinery can alter the result. Chemicals are used

in other tests - the use-by date of these chemical agents can alter results. Technicians

run the tests - their training can alter results. The outcome of all tests needs

to be interpreted by a specialist - their expertise can vary.

All

this adds up to a degree of uncertainty and explains why it is very important

to have all results checked by the most knowledgeable person available - and

why second opinions should be sought automatically.

|

The

second important fact about many medical tests:

The value of many of

the medical tests lies in measuring the change in the results, not in the results

themselves.

|

Thus

for PSA tests, it is important to measure the size and speed of any change, since

this gives an indication of the aggressiveness of the disease. To get this measurement

it is necessary to have a series of tests at regular intervals. This may mean

delaying the start of treatment but the information is invaluable.

|

And

the third important fact - mistakes can be made

|

The

medical world does not differ from any other place. Human beings run it and they

can make mistakes. Get copies of all test results - ensure they are yours. If

an unusual result does not relate to other results, have a re-test in case a mistake

has been made.

Collect

and keep the paperwork

Studies show that people who take an interest

in the diagnosis and details of their disease and who involve themselves in the

process of selecting the most suitable treatment have the best chance of recovery.

Appointments

with medical advisors are often confusing and sometimes rather rushed affairs.

Many people feel they do not want to waste their doctor's time and sometimes doctors

give the impression their patients are indeed doing just that. But whether the

time with the medical people is long or short, the information will often be bewildering

or overwhelming. It is considered to be a good idea therefore to:

Make notes before the appointment of all the issues you want to discuss or ask

about;

Make notes before the appointment of all the issues you want to discuss or ask

about;

Attend all appointments with a companion - two heads being better than one for the interpretation of the information;

Attend all appointments with a companion - two heads being better than one for the interpretation of the information;

Take a portable tape recorder to the appointment and record what is said, if the

doctor is agreeable - you will then have time to gain a greater understanding

of what was said when you play back the tape;

Take a portable tape recorder to the appointment and record what is said, if the

doctor is agreeable - you will then have time to gain a greater understanding

of what was said when you play back the tape;

Not be reticent in expressing reservations, asking for the rationale for a suggested

course of action or determining the likely side effects. Ensure that you receive

all the information you will need to make your decision.

Not be reticent in expressing reservations, asking for the rationale for a suggested

course of action or determining the likely side effects. Ensure that you receive

all the information you will need to make your decision.

It

is very important to obtain, study and keep copies of all medical reports.

Try to understand what they say; what they mean. If anything isn't clear, ask

for more information and keep asking until you understand. It may be difficult

for a medical person to reduce the complexities of a diagnosis to simple, non-medical

terms, but you are entitled to this, so keep at it.

|

It

is also a good idea to check reports for factual errors. Even typing errors can

be a cause for concern and lead to misunderstandings. It may not be of great importance

if the report records your age incorrectly. Whether a man is circumcised or uncircumcised

does not affect the diagnosis or choice of treatment. But if this type of detail

is wrong, there may be other errors, on the technical side, that are not so obvious.

Travelling

Companions

The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer affects not

only the man with the disease, but also his wife or partner and family. It is

particularly hard on the womenfolk. A woman is not only concerned about her man,

but also about her own future without him - and often feels guilty about this.

It is much more difficult to deal with these issues alone than it is with the

support of other people. Family and friends should be told and be involved in

the process of sifting information and coming to a decision. A word of warning

here - the help offered by well-meaning people can be somewhat overwhelming at

times, so it may be best to keep the circle of helpers small initially.

Support

groups - terrestrial or in the cyberworld - can provide invaluable encourage-ment

and advice. Most men and their companions who join support groups speak highly

of the comfort in knowing they are not alone, and being able to speak to people

who are on the same journey they are. Even talking to strangers can help - many

men have travelled this way before and most will be only too pleased to pass on

what they have learned. By taking these steps some of the feeling of "aloneness"

is dissipated. It is worth asking your doctor or making enquiries at your local

hospital to find the nearest support group.

Diagnosis with a potentially

life-threatening disease can cause tremendous emotional upset - there is sorrow,

anger, fear for the future and a whole host of aspects that must be worked through.

The combination of these can often lead to the development of clinical depression

which is very difficult to deal with alone. Men are notoriously reluctant to seek

professional help for mental conditions like this but should get to a counsellor.

It will assist in regaining their balance.

If

you have access to the Internet, join one of the discussion lists or forums and

ask questions. The collective knowledge of the men and women on these lists is

substantial and very few questions cannot be answered. Above all, never be concerned

about appearing 'stupid' in asking a question. The only 'stupid' questions

are those not asked.

GETTING

STARTED - THE PROCESS

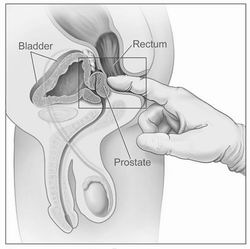

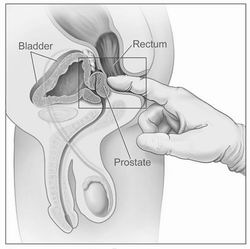

DRE - Digital Rectal Examination

The

first step in the process of getting to the Strange Place is usually what is referred

to as a DRE. This stands for Digital Rectal Examination and is dreaded by most

men. Many refuse to even consider it. Most women cannot understand what the fuss

is about. It is a simple procedure and there is no discomfort when it is done

well - and if the man is relaxed. The examination does not take very long - usually

less than 30 seconds.

If

you have an understanding of where the prostate is located, it is pretty obvious

that the only way it can be reached practically is via the rectum. The doctor inserts

a finger to feel the prostate.

In doing so, the doctor is trying to establish whether there is anything unusual

about the gland: a firmness perhaps, or nodules, or roughness on the surface.

A biopsy may well be ordered if the DRE reveals any abnormal features.

If

you have an understanding of where the prostate is located, it is pretty obvious

that the only way it can be reached practically is via the rectum. The doctor inserts

a finger to feel the prostate.

In doing so, the doctor is trying to establish whether there is anything unusual

about the gland: a firmness perhaps, or nodules, or roughness on the surface.

A biopsy may well be ordered if the DRE reveals any abnormal features.

In

days gone by the DRE was virtually the only way in which prostate cancer was diagnosed,

unless there were symptoms. This method of diagnosis is not very accurate because

of the limits imposed by the examination. For one thing the doctor can only feel

one side of the gland; for another, the examining finger is clad in a glove.

The

DRE (Digital Rectal Examination)

There

are considerable differences of opinion in the recommendations of various authorities

around the world, but broadly speaking, the DRE should be a standard item on an

inclusive health checklist for men over 50 years old, or for men over 40 years

of age if they are 'at risk' - for example if breast or prostate cancer has been

diagnosed in parents, aunts, uncles or siblings. In the US Afro-American men are

seen to be at risk because of the high incidence of prostate cancer amongst these

men.

PSA - Prostate Specific Antigen

This

is the most widely used test for detecting prostate cancer today. It is simple

to do. A small sample of blood is taken, usually from a vein in the arm, and is

tested for the presence of PSA (Prostate Specific Antigen). This is an enzyme

initially thought to be formed only by the prostate gland - hence "prostate specific".

It is now known that very small quantities of the enzyme are produced by other

glands - and even by women.

The laboratory testing the blood will report

a number, which reflects the level of PSA in the blood, usually in nanograms per

millilitre (ng/ml). A nanogram is one billionth of a gram; a millilitre is one

thousandth of a litre. The method used to measure these very small amounts differs

between the manufacturers of the testing equipment and the results produced vary

considerably. Although manufacturers agreed to calibrate their equipment to produce

comparable results, this is often not done in practice. It is best if you can

have all tests run by the same laboratory using the same equipment. Most laboratories

will only guarantee accuracy to within 80%.

IMPORTANT

INFORMATION REGARDING PSA

PSA

is not a prostate cancer specific marker. PSA levels can be elevated by

a number of causes, from infection to physical activities. So it is very important

to investigate the cause of any elevated PSA reported and not to assume that it

is prostate cancer. In one reported case, a man with a PSA of 362 ng/ml was found

to have an infection that responded to treatment - it was NOT prostate cancer.

Although a PSA of 4.0 ng/ml is regarded as "normal", only a minority of men -

between 25% and 35% - with a reading higher than that will be diagnosed as having

prostate cancer. Men with a PSA level lower than the "normal" were biopsied in

one study - many had positive results.

|

The scale of measurement is unlimited and PSA readings of over 1,000 ng/ml are

not unheard of. One man in the United States had a PSA reading of 3,552 ng/ml

in 1991, which climbed to 12,600 ng/ml in 1992. In 1999 his PSA was down to 109

ng/ml after treatment and he was still working as a commercial pilot on a large

American cargo airline, subsequently rising to Chief Pilot before retiring in

2009. It is unusual for a man to survive so long with such high levels of PSA

- this level is usually associated with a very aggressive tumour. Just another

example of the Golden Rule.

When the PSA test was introduced as a diagnostic

tool in 1990, a level of 10 ng/ml was considered "normal" and anything higher

required further investigation. This figure was subsequently reduced to 4.0 ng/ml,

which is regarded as "normal" in most countries. In the US there is a move to

lower the measure to 2.6 ng/ml and there is even some pressure to go to 1.25 ng/ml

as a "standard". Prostate cancer will not be found in roughly 65% of men with

a PSA higher than 2.6 ng/ml. In many cases where prostate cancer is discovered

after an "abnormal" PSA test, the tumour will be regarded as "insignificant" or

"very low risk" and may not need immediate treatment.

There is another

PSA test - the fPSA, PSA II or Free PSA test. This test refers to the amount of

what is referred to as "unbound" or "free" PSA in a sample of blood and is discussed

below.

The most common causes of an elevated PSA are prostatitis (an infection

of the prostate), a bladder infection, or BPH (Benign Prostate Hyperplasia). This

last condition affects most men over 50 years of age and is not deadly. There

is little which can be done to reduce the effect of BPH on the PSA level in the

short term, but any infection should be treated before a second PSA test is carried

out. Acute prostatitis can cause the PSA levels to rise to five to seven times

the normal level for up to six weeks. Infections of the bladder and prostate are

often very difficult to deal with.

It is recommended that blood for PSA

testing should be drawn as early in the day as is convenient and preferably before

eating. Physical activities can affect the PSA level, and these should be avoided

before drawing the blood. Examples of physical activities to avoid include:

DRE (Digital Rectal Examination). Although doctors often carry out the

DRE before drawing blood, they should reverse these procedures.

DRE (Digital Rectal Examination). Although doctors often carry out the

DRE before drawing blood, they should reverse these procedures.

Sexual activity: Ejaculation can elevate PSA levels for up to 48 hours after it has taken place.

Sexual activity: Ejaculation can elevate PSA levels for up to 48 hours after it has taken place.

Cycling or motor

cycling: This can increase levels up to three times for up to a week, depending

on how strenuous the cycling is. This includes use of an exercise bicycle.

Cycling or motor

cycling: This can increase levels up to three times for up to a week, depending

on how strenuous the cycling is. This includes use of an exercise bicycle.

Alcohol and coffee:

Both can irritate the prostate and should be avoided for 48 hours prior to blood

being drawn.

Alcohol and coffee:

Both can irritate the prostate and should be avoided for 48 hours prior to blood

being drawn.

If any PSA result is between 4 and 10 ng/ml, a second test

should be run - the so-called fPSA, PSA II or Free PSA test. Some laboratories

will do this automatically, while others require a specific request since the

cost of the fPSA test is higher than the PSA test alone. The result of this test

will usually be shown as a percentage of the total PSA measured and is a valuable

part of the diagnostic process. The risk of cancer being present varies in inverse

proportion to the percentage shown. So the higher the percentage, the less chance

of the PSA being caused by prostate cancer. An fPSA of over 25% would mean that

the most likely cause of the elevated PSA is not prostate cancer; an fPSA level

of under 15% will point to prostate cancer as being potentially the main cause

of the elevated PSA. If the fPSA level is high, alternative causes of the elevated

total PSA level should be investigated before a biopsy is undertaken, since there

are some risks associated with biopsy.

PSA levels can also vary significantly

for no obvious reason. It is therefore usually important to have a series of PSA

tests done to establish the average level before moving on to the next important

test, which is the biopsy. Many men monitor their PSA levels for some years, watching

for any upward trend in the numbers.

There

are two commonly used measures PSADT (PSA Doubling Time) and PSA Velocity (PSAV).

The first looks at the time the PSA takes to double or it projects an estimated

doubling time. The more rapid the PSADT, the more likely it is that prostate cancer

is the cause of the high PSA result. So, a PSADT measured in months certainly

requires investigation; a PSADT measured in years may be watched closely for some

time further without any further direct intervention.

The

second measure is PSAV (PSA Velocity) which looks at sequential increases in values

of the PSA levels - if the increases are greater than a target figure (usually

0.75 ng/ml per year) further investigation may be warranted. It is important to

note that if PSA values fluctuate up and down, it is far more likely that the

cause will be infection or BPH - PSA values associated with prostate cancer tend

to increase consistently.

Finally

there is a school of thought that PSA density should be considered. This is measured

by taking the PSA level and dividing it by the volume of the gland. The result

is expressed in ng/ml/gm and the lower the figure the better. As an example, if

a man has a PSA of 5.6 ng/ml and has a large gland estimated at 65 gm, his PSA

density would be 0.086 ng/ml/gm, indicating that much of the PSA is generated

by the normal cells in the large gland. A PSA density of over 0.15 ng/ml/gm may

require further investigation.

Biopsy

If the DRE (Digital Rectal Examination) and/or the PSA tests indicate

the possibility of cancer cells being in the prostate, the next step is to biopsy

the gland - taking samples to examine under a microscope. A spring loaded biopsy

"gun" is inserted into the rectum and very fine needles are 'shot' into the gland

to collect samples. The number of needles used may vary. Usually there are twelve.

In the past six needles were used. Up to 100 needles may be used in what is termed

a 'saturation' or 'mapping' procedure intended to establish the precise site of

any tumor. This is an unusual procedure and would rarely be undertaken in an initial

biopsy, but rather when a focussed treatment such as Cryotherapy or HIFU is being

planned.

The

biopsy procedure is uncomfortable - the procedure has been described rather like

being kicked hard in the backside. Some men have reported considerable pain and

it is wise to ask for an anesthetic spray or other pain deadening methods. For

some reason many doctors do not offer this, and some are even reluctant to do

so even when asked. An ultrasound device is often used to establish whether there

are any specific areas to be investigated. If any are identified, the biopsy "gun"

is guided to these areas. If there is no specific target, the samples are taken

in a standard pattern. Before the biopsy is done, confirmation should be sought

that the samples will be clearly identified by site when the biopsy report is

completed. This is not always done.

One

of the developments in biopsy procedures is the use of Colour Doppler Ultrasound.

Some manufacturers of this equipment claim it can identify tumours without the

necessity of biopsy procedures, but the more general view is that the procedure

can be used to identify potential tumour sites more clearly and to guide the biopsy

needles to those sites. Regrettably very few establishments use this procedure,

which produces more definitive results.

|

CAN

BIOPSY PROCEDURES SPREAD THE CANCER?

Concerns

are often expressed about side effects from the biopsy procedure. The most worrisome

of these is the speculation that the entry of the needles might cause any cancer

to spread. There is no firm evidence of this happening, although there is a view

that it is a possibility. It is clear that there can be an increase of cancer

cells in circulation in the bloodstream after a biopsy. The unresolved argument

concerns the possibility of these cells lodging in other parts of the body and

establishing a metastasised disease.

Given

the number of biopsy procedures carried out, especially in the United States,

since the widespread use of PSA testing began there would be the expectation,

if this concern was justified, that the incidence of prostate cancer would rise

sharply. It has not but has in fact reduced.

|

There

are usually some short-term side effects. The prostate bleeds after the procedure,

so both urine and ejaculate will usually be bloody for some time. Initially the

urine will often be the colour of Cabernet Sauvignon, but will fade to Rosé. The

long-term side effects can include erectile dysfunction, but, as said previously,

they are very rarely reported. One study puts their incidence at less than 3%.

Because the biopsy needles pass through the lower bowel on their way to the prostate,

there is a chance of infection so it is important to take the antibiotics, which

will be prescribed before the procedure is carried out. Most samples taken by

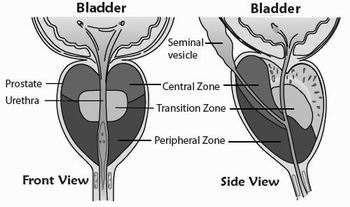

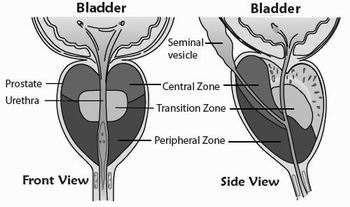

needle biopsy come from what is termed the peripheral zone of the gland

Samples

are also submitted for analysis when men have the procedure known as a TURP (Transurethral

Resection of the Prostate), the common way of dealing with BPH (Benign Prostatic

Hyperplasia). This material is examined for cancer cells and if found these are

graded in the same way as the samples from the biopsy procedure described above.

If there is a positive diagnosis following a TURP, the material will have come

from the transition zone of the gland. The majority of tumours in this area have

low Gleason scores and will probably not progress to become life threatening.

This may make the man a candidate for what is termed Active Surveillance or watchful

waiting.

Gleason Grades

Illustration of Gleason Grades from 1 to 5

The

biopsy samples are examined in a pathology laboratory. The pathologist or technician

will be looking for groups of abnormal cells - cells that have lost their natural

shape and have created unusual glandular patterns. The first (prime) focus is

on the abnormal patterns making up more than 50% of the sample. The second (secondary)

and third (tertiary) foci are on abnormal glandular patterns that make up less

than 50% of the sample. Not all abnormalities are identified as cancer - there

are at least four conditions that can be confused with adenocarcinoma, the most

common form of prostate cancer. Reference is also sometimes made to 'atypical'

cells. This merely means that they are not normal, but does not necessarily mean

they are cancerous.

The

biopsy samples are examined in a pathology laboratory. The pathologist or technician

will be looking for groups of abnormal cells - cells that have lost their natural

shape and have created unusual glandular patterns. The first (prime) focus is

on the abnormal patterns making up more than 50% of the sample. The second (secondary)

and third (tertiary) foci are on abnormal glandular patterns that make up less

than 50% of the sample. Not all abnormalities are identified as cancer - there

are at least four conditions that can be confused with adenocarcinoma, the most

common form of prostate cancer. Reference is also sometimes made to 'atypical'

cells. This merely means that they are not normal, but does not necessarily mean

they are cancerous.

Any cells with patterns appearing to be cancerous are

evaluated using a scale known as the Gleason Grade (GG) which was established

in the 1960s and which had five grades. Patterns that were well differentiated,

but abnormal, were graded as 1; at the other end of the scale, poorly differentiated

patterns were graded as 5. Healthy glandular tissue is well differentiated, so

a Gleason Grade of 5 is bad news: a Grade of 1 is good news.

Originally,

after each focus is graded, the primary and secondary Gleason Grades were added

together to establish a Gleason Score (GS). The Gleason Score therefore was a

scale that ran from 2 from (1+1=2=good) to 10 (5+5=10=(bad). Typical examples

of Gleason Scores (and the most common) would be shown as GS 3+2=5 or GS 3+3=6.

A score of 6 was the mid-point in the aggressiveness rating.

Note the

difference between a Gleason Grade and a Gleason Score

(which is the sum of the two grades.)

In

January 2010, announcements were made in the United States that significant changes

had been agreed by the International Society of Urological Pathology in

the way in which prostate cancer tumours were graded internationally.

The

key points of these changes were:

Gleason grades 1 and 2 will "rarely if ever" be classified from a needle biopsy

- they might be from "chips" resulting from a TURP (transurethral resection of

the prostate)

Gleason grades 1 and 2 will "rarely if ever" be classified from a needle biopsy

- they might be from "chips" resulting from a TURP (transurethral resection of

the prostate)

Some prostate cancers

that would originally have been classified as a Gleason grade 2 cancers should

now be graded 3 cancers

Some prostate cancers

that would originally have been classified as a Gleason grade 2 cancers should

now be graded 3 cancers

Some prostate cancers

that would originally have been classified as a Gleason grade 3 cancers should

now be graded 4 cancers

Some prostate cancers

that would originally have been classified as a Gleason grade 3 cancers should

now be graded 4 cancers

More attention should

be paid to any tertiary Gleason grade 4 and 5 cancers in all specimens

More attention should

be paid to any tertiary Gleason grade 4 and 5 cancers in all specimens

It

is not clear how the tertiary grades will be used since the value of this information

in making clinical decisions is still controversial. The recommendation is that

when biopsy cores show differing grades of prostate cancer, the pathologist should

report the Gleason grades for each core individually, and the highest individual

Gleason grade should be used in making decisions about treatment - regardless

of the percentage of the involvement of that grade overall. (In other words if

the patient has one core with Gleason 3 + 3 = 6 disease in 60 percent of the core;

a second core showing Gleason 3 + 3 = 6 disease in 48 percent of the core; and

a third positive core showing Gleason 3 + 4 = 7 disease in just 5 percent of the

core, he should still be managed as though he has Gleason 3 + 4 = 7 disease.)

These

announcements codified the changes that had been occurring since 2002 - the so

called "Gleason Migration" - which saw very few diagnoses with Gleason Scores

lower than 3+3=6. The immediate effects of the changes are:

The range of Gleason Scores, previously a scale of 2 - 10 is now a scale of 6

- 10

The range of Gleason Scores, previously a scale of 2 - 10 is now a scale of 6

- 10

A diagnosis of Gleason Score 6 is therefore the lowest grade of prostate cancer

A diagnosis of Gleason Score 6 is therefore the lowest grade of prostate cancer

There will be an increase in Gleason Score 7 diagnoses

There will be an increase in Gleason Score 7 diagnoses

There will be more focus on the differences between what have been termed Gleason

Score 7a -3+4=7 and Gleason Score 7b - 4+3=7

There will be more focus on the differences between what have been termed Gleason

Score 7a -3+4=7 and Gleason Score 7b - 4+3=7

There will be further subdivisions of 'risk' taking into account PSA levels and

the size and number of positive biopsy specimens - termed Very Low Risk:

Low Risk: Intermediate Risk: High Risk for the present

There will be further subdivisions of 'risk' taking into account PSA levels and

the size and number of positive biopsy specimens - termed Very Low Risk:

Low Risk: Intermediate Risk: High Risk for the present

Care must be taken in interpreting data from nomograms (such as the Partin's Tables)

which are used to estimate various probabilities of outcomes based on the specifics

of diagnosis. Initially these nomograms will use old data.

Care must be taken in interpreting data from nomograms (such as the Partin's Tables)

which are used to estimate various probabilities of outcomes based on the specifics

of diagnosis. Initially these nomograms will use old data.

The

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has also announced updates

to the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines for Oncology™ for Prostate Cancer which

incorporate these revisions to the Gleason Grading and Scoring system.

IMPORTANT

INFORMATION ON BIOPSY AND GLEASON GRADES

The

process of grading abnormal cells is a subjective one but can

have a significant influence on the chosen method of treatment.

Accuracy

in the grading will depend on a number of things, including the experience of

the person doing the grading. It

is very important that any Gleason Score is confirmed by getting a second opinion

from at least one independent laboratory. If

the prostate gland is removed surgically, the Gleason Score may change. This post-operative

Gleason Score may be higher or lower than the biopsy score. It will be more accurate

because the entire gland can be examined. A biopsy examines a small sample.

|

Unfortunately

there are no standard procedures for reporting on biopsy results. It is important

for the samples collected in the biopsy procedure to be clearly labelled so the

area where any cancerous cells are found can be identified. This makes focussed

treatment easier. Some laboratories do not do this automatically, so it is worth

insisting upon it when arranging for the biopsy. A good report will show a detail

such as:

The part

of the prostate where the material being reported on was collected;

The part

of the prostate where the material being reported on was collected;

The amount of abnormal material in the total sample;

The amount of abnormal material in the total sample;

The percentages of material which relates to the Gleason Grades reported;

The percentages of material which relates to the Gleason Grades reported;

Any evidence of neural invasion or spread to tissue beyond the prostate capsule;

Any evidence of neural invasion or spread to tissue beyond the prostate capsule;

The presence or absence of PIN (prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia).

The presence or absence of PIN (prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia).

The

reference above to PIN is important. PIN can occur in a prostate and because it

is similar in structure to adenocarcinoma (prostate cancer) it is sometimes mistaken

for that condition. PIN is not malignant. There is a view in some parts of the

medical profession that PIN may be a forerunner to prostate cancer but this has

not yet been demonstrated conclusively. At least three other conditions exist

where abnormal cells can be mistaken for adenocarcinoma - hence the importance

of second expert opinions.

Additional Tests:

Blood Tests and Scans

Treatment options can vary depending on whether

the disease is contained within the gland or has moved on. So, if the results

from the biopsy are positive - meaning that prostate cancer has been reported

- then it is customary to have further tests to try to establish if the disease

has gone beyond the capsule of the prostate gland. Some tests are not really diagnostic

but are useful to establish a base line for tracking future developments. In addition

to the tests, nomograms such as the Partin Tables (discussed further on) can be

used to estimate probabilities of the disease having spread.

At this stage

it might be worth having a quick overview of how prostate cancer spreads.

Diversion

- Metastasis, or how prostate cancer spreads

The normal progression

of prostate cancer is to move out of the prostate as the cancer grows. The first

step is often to penetrate the capsule of soft tissue surrounding the prostate

gland. This may be accomplished by the cancer tracking the nerves, in much the

same way as the roots of a tree will follow pipes. Having penetrated the capsule,

the spread will often be into adjacent tissue, specifically the seminal vesicles

(glands on each side of the bladder) and the lymph nodes (an integral part of

the immune system).

From these sites the disease can migrate to other organs,

although the normal target is the bone, specifically the pelvic girdle and spine.

The process of this spreading of the disease beyond the capsule is called metastasis.

Commonly a metastasised tumour is simply referred to as "mets" as in "mets to

the bone" or "liver mets".

Back to the additional tests.

Blood

Tests

PAP (Prostatic Acid Phosphatase)

This

test should not be confused with the better-known Pap Smear women have for the

detection of cervical cancer. It is a test measuring an enzyme in the blood.

Few

specialists now recommend a PAP (Prostatic Acid Phosphatase) test after diagnosis,

although it was once a standard test. It is not very accurate but it can give

an indication of the possibility of the tumour having spread beyond the capsule

- the soft tissue that surrounds the gland. The test, like the PSA test, is affected

by sexual activity. It should not be done within 48 hours of ejaculation and not

until at least six weeks after biopsy.

There is no universally accepted

standard regarding the calibration of results, so if PAP results are used for

tracking any developments, the blood should always be sent to the same laboratory.

Although there is a high number of false negatives - about 25% of men with metastases

do not have elevated PAP numbers - anyone with an elevated PAP score should be

aware that this may make surgery a poor choice. Studies indicate men with high

PAP scores can have up to four times the risk of a relapse after surgery.

Other

markers

The presence of higher than normal levels of CGA (Chromagranin

A) in the blood can be an indicator of a more aggressive form of prostate cancer.

This is especially true if it is found in conjunction with elevated scores in

other markers such as NSE (Neuron Specific Enolase) or CEA (Carcinoembryonic antigen).

These markers can be used to track the effectiveness of treatment and it is important

to view them as a series and not to take one isolated elevated score as a poor

indicator.

Scans - X-rays, bone scans, CAT scans

and MRI

Scans are done in order to try to see what, if any, spread

there is beyond the capsule. The value of some of these scans is doubtful in many

cases. Some leading practitioners consider the automatic ordering of CAT and bone

scans, which occurs frequently, as a waste of money. Their necessity should be

established before the scans are undertaken.

The Partin Tables (described

further on) can help in making this decision. The chances of there being metastases

to the bone are remote with a small volume, low-grade (Gleason Grade 5 or lower)

tumour. However, there is a high correlation between high Gleason Grades (8 and

above), a large tumour and the extent the disease has moved beyond the gland.

According to one leading authority there is virtually no possibility of metastasis

occurring until the tumour reaches a critical mass of about 12 ccs. The average

prostate gland is about 25 ccs, so in this view about half the gland would be

occupied by cancer cells before metastasis occurred. There would therefore usually

be a positive DRE (Digital Rectal Examination) and a palpable mass. A leading

expert has also expressed the view that metastasis will not occur if the PSA is

less than 50 ng/ml, unless the Gleason Score is very high - greater than 8.

X-ray

X-rays

are usually undertaken as a matter of course. However, the chances of any signs

of spread being shown, using X-rays alone, are slim. If any of the other scans

are being run, there is probably little point in having an X-ray. Many people

strongly believe in avoiding any unnecessary exposure to X-ray to minimise the

chance of cell damage.

Bone

Scans

Bone scans fall under the general term of nuclear medicine. The

way in which the bone scan works is the reverse of a CAT scan or an X-ray. In

conventional X-ray or CAT scan examinations, the radiation comes out of a machine

and then passes through the patient's body. Nuclear medicine examinations, however,

use the opposite approach. A radioactive material is introduced into the patient's

body (usually by injection), and is then detected by a machine called a gamma

camera. The procedure for a bone scan involves nuclear material injected into

a vein (usually in the arm). There is a wait of two to three hours for the material

to circulate in the system. The person being examined then lies on a special table

and the gamma cameras (one above and one below) slowly track down the length of

the body. The entire procedure takes between 30 and 60 minutes.

Bone metastases

are usually associated with advanced prostate cancer, so bone scans are not considered

essential for early stage disease. For men with a PSA of less than 10 and a Gleason

Grade of 6 or less, the chances of the disease having metastasised to the bone

has been estimated at less than 1% - which is equivalent to zero in normal terms.

Some people are concerned about the introduction of nuclear material into

the body, but it is said that the radiation from this procedure is similar to

that from a normal X-ray. The material is quickly cleared from the body. There

is nothing painful about the procedure - apart from the injection, but the table

upon which the person lies is made of metal and can be very cold, especially in

winter, creating a degree of discomfort.

|

IMPORTANT

POINT REGARDING BONE SCANS

The

procedure is not cancer specific. It highlights local changes in bone metabolism,

not cancer as such. So it will also highlight old fracture sites and even arthritis.

Author Michael Korda, in his book Man To Man, describes the fear a positive

bone scan raised. This showed what seemed to be clear signs of metastasis to his

collarbone. It was only some time later that he remembered he had fractured his

collarbone years before.

|

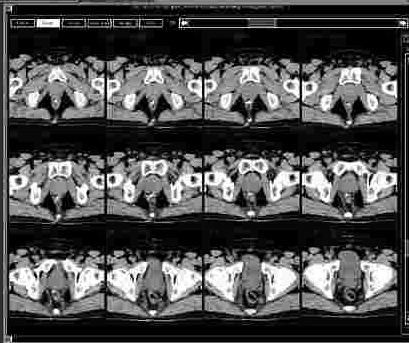

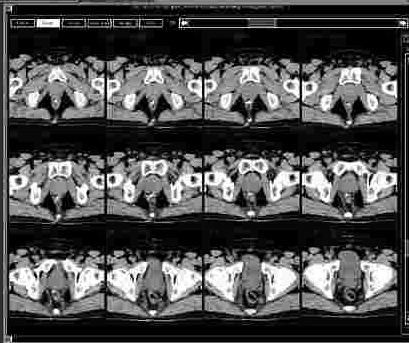

CAT

(Computer Axial Tomography)

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging)

Although

these two scans use differing technology, they are similar in their output. Both

create a series of images, in effect showing views of the organ being examined

in "slices". The CAT scan uses X-rays to create the images. The MRI scan uses

a very strong magnetic field for this purpose. The MRI images can be enhanced

by the use of an endorectal coil. This is a small device inserted into the rectum,

which generates secondary fields.

Both

examinations can be a little intimidating for those having them for the first

time. The person being scanned lies on a small trolley, which enables them to

be moved into a large cylindrical structure containing the scanning machinery.

There is very little room in the older cylinders, especially for larger men, and

a feeling of claustrophobia can result. Newer machinery has more room. The MRI

process is noisy and operators should provide earplugs or headphones. There is

nothing painful about either procedures - just a degree of discomfort from remaining

immobilised during the scan, and the noise.

Both

examinations can be a little intimidating for those having them for the first

time. The person being scanned lies on a small trolley, which enables them to

be moved into a large cylindrical structure containing the scanning machinery.

There is very little room in the older cylinders, especially for larger men, and

a feeling of claustrophobia can result. Newer machinery has more room. The MRI

process is noisy and operators should provide earplugs or headphones. There is

nothing painful about either procedures - just a degree of discomfort from remaining

immobilised during the scan, and the noise.

Series from a pelvic scan

Some

experts feel that CAT scans are only of value in the diagnostic process of advanced

prostate cancer, which is usually associated with PSA readings of 50 ng/ml or

higher and Gleason Scores greater than 8. CAT scans are highly insensitive in

detecting disease in the lymph nodes, and valueless in most patients in detecting

penetration of the capsule, which is usually the first stage of progression of

the disease.

MRI scans with the endorectal coil can be much more useful

but even then will only be associated with an accuracy rate of between 75% and

90%. Both types of scan have high false positive and false negative results. In

other words they will identify tumours which don't exist or miss ones which do

exist.

STAGING

AND DIAGNOSIS

The final step in this part of the journey through the

Forest of Fear is to stage the disease. This summarises the results of

all the tests and results in the Diagnosis. It is very important to achieve as

accurate a staging as possible because, as will be seen, some forms of treatment

are more suitable for some stages than for others.

Until fairly recently

there were many systems of staging. The best known was probably the Whitmore-Jewett

system, which showed four stages defined as A, B, C, D. The current system, used

almost universally, is referred to as the TNM system which has four T

stages, which are then subdivided into a number of sub-sets. These are followed

by the N and M stages, which are also subdivided. The main divisions

are as shown below, although there may be some variations in some definitions:

T

1: The tumour is discovered "incidentally". This is usually in connection

with a TURP (Transurethral Resection of the Prostate) done to relieve the symptoms

of BPH (Benign Prostate Hyperplasia). The material produced by the TURP is subjected

to pathology analysis and if cancer is detected, the disease is staged as T1a

or T1b depending on the amount of material exhibiting malignancy and the Gleason

Score. If the tumour is discovered in the course of a biopsy following an elevated

PSA test and if there are no other symptoms, then the stage is T1c.

T

2: For this stage, the tumour must be palpable. This means that the

doctor carrying out the DRE (Digital Rectal Examination) must be able to feel

the tumour. If the tumour occupies less than half of one lobe of the gland the

disease is staged as T2a. If the tumour occupies more than half of one lobe, the

disease is staged as T2b. When the disease can be felt in both lobes it is staged

T2c.

Illustration of Stage T2

T

3: A diagnosis of stage T3 disease requires penetration of the capsule

- the soft tissue surrounding the prostate. Stage T3a disease has no evidence

of involvement of other tissue and has penetration on one side of the capsule

only. Stage T3b is similar to T3a except there is penetration on both sides of

the capsule. Stage T3c indicates penetration from one or both sides, but with

the involvement of the seminal vesicles - located on either side of the bladder

T 4: In this stage, the

tumour has escaped from the capsule and the seminal vesicles, although it is still

contained in the immediate area of the prostate gland. A stage T4a disease will

have invaded the bladder neck or sphincter or the rectum. A stage T4b disease

will have invaded the levator muscles or may be fixed to the pelvic wall.

N+:

Disease staged as N+ will have evidence of spread to the pelvic lymph nodes.

If there is no sign of this spread the stage will be shown as N0. If the presence

of the cancer in the lymph nodes cannot be assessed the staging will be NX. Sometimes

three stages of N (N1, N2, N3) are used to denote the extent of the spread into

the lymph nodes.

M+: Disease staged as M+ will

have evidence of spread beyond the pelvic lymph nodes; in other words, the disease

has metastasised. If there is no sign of this spread the stage will be shown as

M0. If the presence of distant metastases cannot be assessed the staging will

be MX. Sometimes three stages of M (M1, M2, M3) are used to denote the extent

of the metastases.

And

that's how to get to DIAGNOSIS. Anyone who has got here will be able to

relate better to the denizens of this Strange Place because all will have the

"numbers" that define their diagnosis. The normal sequence of these "numbers"

is PSA, GS (Gleason Score) and Stage. A typical "number" might be PSA 7.2:

GS 3+2=5: Stage T2bNXM0. This would relate to a man who has a slightly

elevated PSA of 7.2 ng/ml, a Gleason Score of 5 that indicates a relatively non-aggressive

tumour, but a tumour occupying more than half of one lobe of his prostate. It

is not clear whether the tumour has spread to the lymph nodes but there is no

sign of metastasis beyond the pelvic area.

Simple now you know how to

read the language in the Strange Place !!

Back to top

GO

NOW to Part 3 - Beyond Diagnosis - The Desert of Doubt

If

you have an understanding of where the prostate is located, it is pretty obvious

that the only way it can be reached practically is via the rectum. The doctor inserts

a finger to feel the prostate.

In doing so, the doctor is trying to establish whether there is anything unusual

about the gland: a firmness perhaps, or nodules, or roughness on the surface.

A biopsy may well be ordered if the DRE reveals any abnormal features.

If

you have an understanding of where the prostate is located, it is pretty obvious

that the only way it can be reached practically is via the rectum. The doctor inserts

a finger to feel the prostate.

In doing so, the doctor is trying to establish whether there is anything unusual

about the gland: a firmness perhaps, or nodules, or roughness on the surface.

A biopsy may well be ordered if the DRE reveals any abnormal features.

The

biopsy samples are examined in a pathology laboratory. The pathologist or technician

will be looking for groups of abnormal cells - cells that have lost their natural

shape and have created unusual glandular patterns. The first (prime) focus is

on the abnormal patterns making up more than 50% of the sample. The second (secondary)

and third (tertiary) foci are on abnormal glandular patterns that make up less

than 50% of the sample. Not all abnormalities are identified as cancer - there

are at least four conditions that can be confused with adenocarcinoma, the most

common form of prostate cancer. Reference is also sometimes made to 'atypical'

cells. This merely means that they are not normal, but does not necessarily mean

they are cancerous.

The

biopsy samples are examined in a pathology laboratory. The pathologist or technician

will be looking for groups of abnormal cells - cells that have lost their natural

shape and have created unusual glandular patterns. The first (prime) focus is

on the abnormal patterns making up more than 50% of the sample. The second (secondary)

and third (tertiary) foci are on abnormal glandular patterns that make up less

than 50% of the sample. Not all abnormalities are identified as cancer - there

are at least four conditions that can be confused with adenocarcinoma, the most

common form of prostate cancer. Reference is also sometimes made to 'atypical'

cells. This merely means that they are not normal, but does not necessarily mean

they are cancerous. Both

examinations can be a little intimidating for those having them for the first

time. The person being scanned lies on a small trolley, which enables them to

be moved into a large cylindrical structure containing the scanning machinery.

There is very little room in the older cylinders, especially for larger men, and

a feeling of claustrophobia can result. Newer machinery has more room. The MRI

process is noisy and operators should provide earplugs or headphones. There is

nothing painful about either procedures - just a degree of discomfort from remaining

immobilised during the scan, and the noise.

Both

examinations can be a little intimidating for those having them for the first

time. The person being scanned lies on a small trolley, which enables them to

be moved into a large cylindrical structure containing the scanning machinery.

There is very little room in the older cylinders, especially for larger men, and

a feeling of claustrophobia can result. Newer machinery has more room. The MRI

process is noisy and operators should provide earplugs or headphones. There is

nothing painful about either procedures - just a degree of discomfort from remaining

immobilised during the scan, and the noise.